Architecture used to come from the ground. For generations it was the product of the geology beneath them and the materials that grew out of the resultant landscapes. In a place devoid of trees, Icelanders historically built with turf and basalt, or other volcanic rock , but with urbanism, came concrete; even the farmhouses were built of concrete.

.

Nowadays however most building materials are imported and increasingly down-town Reyjavik resembles down-town Dublin, Copenhagen etc.. Even in those days when Iceland had its own cement plant the raw materials were imported. So now Icelandic Architecture comes in shipping containers.

For many of the architects I spoke to, this in an inevitable consequence of the global building materials market – where materials, like cement, are a trading commodity – part of an industry more concerned with its international share prices than with local relevance or environmental impact. Architects do what they can do to push back at the inevitable pressure to buy cheaper imported materials by building relationships with local workmen; trying where they can to use local site materials or reuse waste. But it’s not consistent and requires commitment beyond the day to day work. It’s difficult to know where the answers to this problem lie – it certainly needs change at policy and an increased public awareness to alter such global pressures, and it needs a change in attitude to materials in the next generation of Designers and Architects (probably the easiest aspect though nevertheless necessary)

So it’s good to see that Design Programme in the University of the Arts has already a highly innovative attitude to materials developed over the last few years (under the guidance of Rúna Thors, Designer and Programme Director and Tinna Gunnarsdóttir , Designer and Professor of Design ). Students are encouraged to experiment with local materials to test the limits of what is possible. At the time I visited they were working with the soil and rock from a nearby mountain and I was lucky enough to hear about the physical and philosophical nature of their design approach.

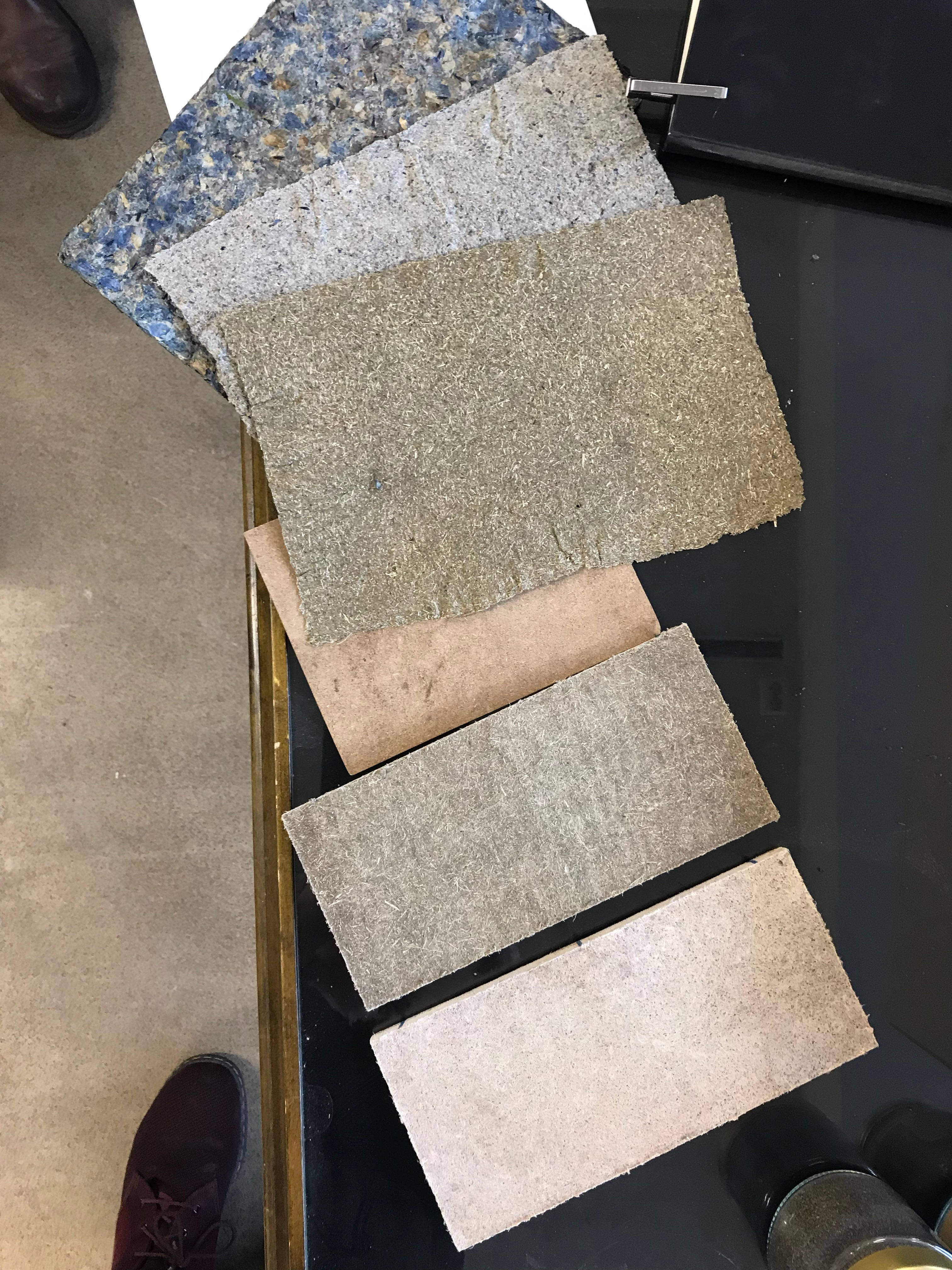

Two of the students, Elín Sigríður Harðardóttir and Inga Kristín Guðlaugsdóttir, also talked to me about an earlier award winning project they had developed – the Lupin Project – where they experimented with the Lupin Flower (an invasive species in Iceland) to produce a variety of outcomes, including a fibre-board. The same Design programme experimented a few years previously with local willow, resulting in a range of products such as pigments for dying, rope and paper.

So University is obviously part of a process to stimulate discussions and awareness within younger generations of designers and architects. I was fortunate to meet some practicing designers who take this ethos into their work: Brynhildur Palsdottir (designer) and Magnea Gudmundsdottir (architect). Together with other colleagues they are engaged in funded research on the facades of Reyjavik. It’s not yet clear where their research will take them but their enthusiasm and creativity for the challenges of building materials in Iceland is palpable.

I also passed the shop window of the young design office Portland who, at the time I was visiting, were growing moss! A interesting loop back to Studio Granda’s mossy, ice-covered facade of Rekyjavik Town Hall, viewed on the first day of my stay.